The Fleisher Years Chapter 4: Art Sanctuary as Object Lesson (1886 – 1934)

The art and architecture of the Sanctuary has developed in three distinct periods: its initial building as The Church of the Evangelists; its reuse by Samuel Fleisher as the heart of the Graphic Sketch Club; and its continuing evolution as the signature space of Fleisher Art Memorial.

For the interior of his new church, Episcopal priest Henry Robert Percival drew inspiration from his travels abroad. The design of the pulpit was based on those seen in basilicas in Southern Italy, and its marble was imported from abroad. The rood screen, separating the altar from the main sanctuary, was executed in Paris; the Great Wheel stained-glass window was made in Roermont, Holland. Dr. Percival also involved his congregation in decorating the interior. To lend a sense of ownership and personal investment in the completion of the church, the charismatic leader asked members to donate money in memory of a loved one, which would be applied to decorating or completing a specific part of the building—for example, the marbles near the altar, and the porch fronting the church on Catharine Street.

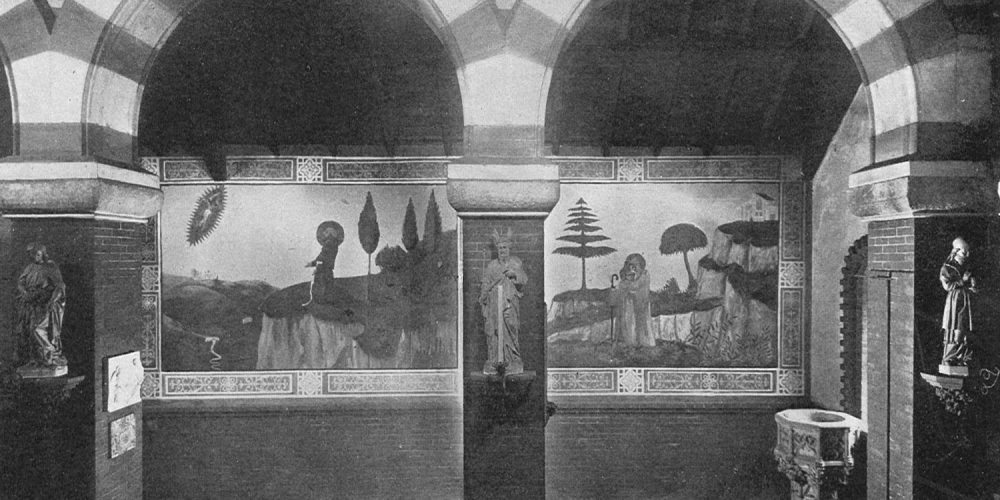

Money for the completion of all the building details was not donated in time before the church closed; to this day, some of the interior column heads remain uncarved and some of the high windows remain unadorned with stained glass. Several church members and friends of Percival also donated their time and talents to painting the interior. The original reredos, or large altarpieces, and the two paintings on the pillars in the central nave of the church were painted by Miss Mary Alice Neilson, a friend and neighbor of Dr. Percival who was also commissioned to paint other reredos over the country. On the left side of the nave, three blind arches were filled with frescoes representing the earth after the fall of Adam and Eve. The other large murals along the nave of the church remain a mystery, but are believed to have been painted by members of the congregation.

The church also commissioned well-known artists to paint murals in the basilica. Robert Henri, graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, created paintings on the walls of the former Lady Chapel (west of the pulpit). Anne Webb, a Germantown resident who studied painting at the Academie Julien in Paris, painted the two murals on either side of the original reredos. Well-known painter and stained glass artist Nicola D’Ascenzo painted the remainder of the murals near the altar—an area known as the chancel—and tiles and marble for the church were gifted by Dr. Henry C. Mercer, founder of the Moravian Tile Company and creator of Fonthill Castle in Doylestown. When Dr. Percival died in 1903, the church he envisioned was vividly realized, though incomplete. His successor, Dr. Charles Wellington Robinson, found the neighborhood changing and the congregation dwindling. By 1911, the church was closed and most moveable objects were removed, including paintings, statuary, pews, and the original reredos.

Developing an Art Sanctuary

In 1922, Samuel Fleisher bought the uninhabited Church of the Evangelists to use as an “art sanctuary” for his Graphic Sketch Club. Fleisher saw the sanctuary functioning as a temple celebrating the power of art—but less like a typical museum and more like an object lesson centered around the art, decoration, and architecture of the building for Graphic Sketch Club students and visitors.

An inscription above the sanctuary’s doorway once read, “To the patrons of the busy streets of Philadelphia: Enter this Sanctuary for rest, meditation, and prayer; may the beauty within speak of the past and ever continuing ways of God.” With this inscription, Fleisher invited passersby into the sanctuary to feel the healing powers of art and beauty imbued with religious aura.

The interior, barren of decoration when Fleisher purchased it, was soon filled with his and his brother’s art collections. Fleisher had acquired medieval statuary, miniatures, and decorative and liturgical objects; his brother also donated a small collection of Russian icons and Persian carpets. Statues stood against the pillars and altars, paintings lined the nave and hung on the columns, and carpets covered the floor in the nave of the sanctuary. While the artwork was not displayed in a typical curatorial fashion, it provided its students and teachers with a broad range of art and architectural learning and teaching tools in an immersive environment.

In addition, Fleisher commissioned new artworks to reinforce the beauty of the sanctuary and the power of art to elevate lives. After admiring Violet Oakley’s murals for the Supreme Court Room in Harrisburg, Fleisher commissioned Oakley to paint a new reredos for the Sanctuary. The monumental painting, called The Life of Moses, was completed in 1929 and dedicated to Fleisher’s mother. The 17-by-8 foot work is an example of Oakley’s eclectic use of art-historical sources, designed as a medieval-style altarpiece inset with images derived from Egyptian wall painting, references to the Renaissance Madonna and Child, and an archaeological approach with a focus on religious subject matter.

Noted in a 1979 Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, Oakley began the process for The Life of Moses by studying Egyptian imagery and motifs in the museums and libraries of Florence while living abroad. She made numerous sketches and studies, and enlisted a four-month-old baby, the son of a neighbor, to pose for the infant Moses. Oakley chose Pharaoh’s daughter holding the infant Moses as the primary subject matter. The central panel depicting an Egyptian princess holding a baby Moses has an inscription from Exodus 2: “And the child grew and he became her song…”

Fleisher expressed discomfort with the visible influence of Christian prototypes, so Oakley introduced the figure of Jocebed–Moses’ mother–teaching the law to the child Moses on the arch above the central panel. On each side of the central image, she illustrated four episodes from the life of Moses. As one of the predella panels, she included a miniature version of the Moses panel that had first attracted Fleisher.

To this day, Oakley’s The Life of Moses remains a central focus of the Sanctuary.

To get updates on events, exhibitions & class information:

"*" indicates required fields